The Western War on Afghan Farmers

Despite decades of prohibitionist policies aimed at reducing the supply of drugs, a booming illicit market is resulting in more drug-related deaths every year, while the policing responses are increasingly violating human rights in their attempt to control the situation. Afghanistan, where civilian drug traffickers are now being targeted by NATO strategic bombers, perhaps best epitomises the increasing violence and diminishing success of the current war on drugs.

The current global drug policy paradigm is one based on strict adherence to the United Nations treaties, which aim to prohibit not only the personal use of drugs, but to exclude them from any broader social and economic role. Data from the latest report from the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) doesn’t paint an encouraging picture for the pursuit of these aims. The number of drug users is rising, as are drug purity and drug-related deaths, while attempts to police the growing market are becoming more desperately violent with diminishing success.

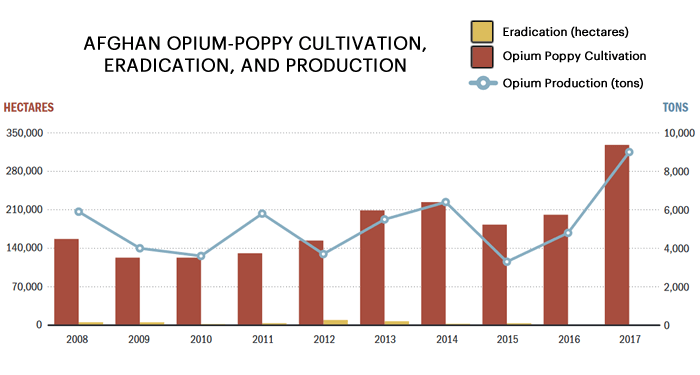

The international heroin trade exemplifies these trends better than any other. In 2017, global production of opium exceeded ten thousand tons – 65% more than the previous year, and the highest output on record. It’s estimated that up to 900 tons of heroin have been produced from last year’s Afghan poppy harvest.

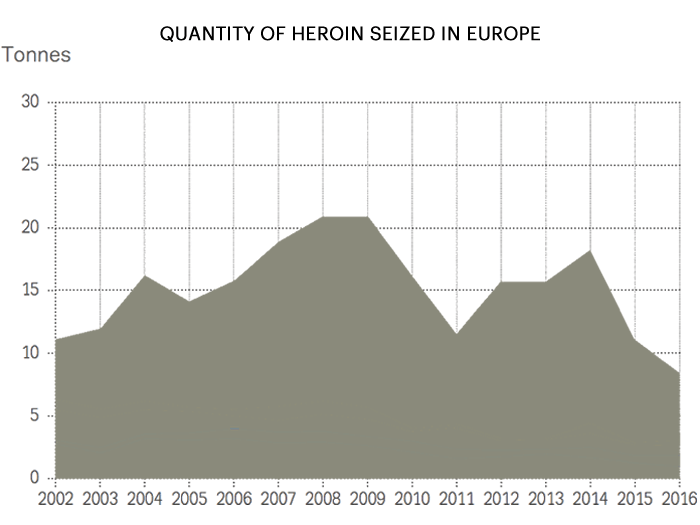

On the borders of Europe, less than 10 tons of this heroin were seized, a number which is decreasing year-on-year. The global policing network which spends over $100b a year to uphold drug prohibition policies is being completely outpaced by the productivity of rural poppy farmers, who the UNODC clarifies grow opium primarily to buy food, afford medical expenses, and pay off debts.

Yearly quantities of heroin seized in Europe (including Turkey and Norway) have declined in recent years (adapted from EMCDDA)

Anti-drug efforts within the borders of Afghanistan are also achieving little success. Disruption of the heroin trade was seen as a vital goal in stabilizing the country and depriving insurgent Taliban forces of funding following the invasion of Afghanistan by the US and its partners in 2003, and coalition forces announced that they would eradicate opium cultivation within 10 years.

Thousands of security operations and other counter-narcotics strategies have since resulted in the seizure of less than 1% of the opium cultivated over the same period, at a cost to the US government – and by extension, the American taxpayer – of over $8.6 billion.

Afghan opium cultivation (red) versus eradication (yellow). Counter-narcotics efforts typically seize or destroy less than 1% of the illicit opium supply (adapted from SIGAR.mil)

Until 2017, the main focus of counter-narcotics was interdiction, whereby the US (and to lesser extent, the UK) military joined with Afghan police forces to intercept and destroy trafficked opium and arrest those suspected to be involved with the trade. Other tactics included alternative development (where farmers were offered incentives to grow other crops) and eradication (where crops were destroyed, either on the ground or through aerial defoliation).

Last year, spurred on by an ongoing opioid epidemic and violent anti-drug rhetoric at home, and a record harvest in Afghanistan, the US administration authorised the military to attack Taliban revenue streams. Specifically, this gave legal authorisation for the US Air Force to bomb suspected opium labs and bazaars, and the unprecedented clearance to assassinate people who were not military combatants. Four days after the UNODC officially announced the record harvest of 2017, the first of these bombings killed over 40 civilians, including the wives and children of suspected opium traders.

The first month of the campaign saw over 20 further bombings, which were claimed by the military to have deprived the Taliban of $16m of revenue. An independent analyst has estimated the value to be closer to $2900. The financial rationale – that forcing civilians to die is justified if it deprives militant groups of funding – is further confounded by the fact that opium revenues also find their way to senior members of the central Afghan government.

The eradication of people and equipment associated with the opium trade may disrupt it in the extreme short-term – opium labs take three or four days to replace – but destructive targeting of the economic livelihood of rural farmers is creating longer-term animosity and instability which will outlast any single poppy harvest. It’s also unlikely that these violent campaigns would reduce opioid overdoses in the US, which are primarily a result of Mexican heroin, Chinese fentanyl, and American oxycodone.

Military footage of an F-22 destroying a suspected Taliban opium-processing plant (Reuters)

The American bombing campaign was endorsed by the UNODC, who first called for NATO to attack the opium industry in 2006. Their most recent report on “peace and security” in Afghanistan notably avoids mention of the ongoing assassinations and bombings and analysis of the possible repercussions. However, the report does mention that only 5% of farmers who had decided to stop cultivating poppies did so because of government anti-narcotic policies.

In addition to being complicit in the targeting of civilians in Afghanistan, the UNODC has directly supported other violent anti-opium campaigns. Until recently, neighbouring Iran hanged hundreds of suspected drug traffickers every year, the vast majority of whom were first-time offenders under the age of 30. The UNODC directly supported these policies using funds from European countries which were officially opposed to the death penalty.

Despite regularly stating that they are committed to improving the “health and welfare of humankind”, the UNODC and international anti-narcotics organisations unfortunately appear, too often, to focus on easily-measurable criteria such as the supply-reduction of drugs and state adherence to international drug policies. This has been much to the detriment of individuals, in Afghanistan and the rest of the world, who face marginalization, imprisonment, and death as a consequence of these policies.

Anti-poppy propaganda poster promoting wheat as an alternative crop (Wikimedia)

“Our analysis reveals no counterdrug program undertaken by the United States, its coalition partners, or the Afghan government resulted in lasting reductions in poppy cultivation or opium production” reads the most recent US government report on Afghan reconstruction. “We found the US government failed to develop and implement counter-narcotics strategies that effectively directed US agencies toward shared, achievable goals.”

The same report acknowledges the alternative strategies which don’t focus on intercepting and destroying opium. Several of these, such as promoting alternative crops, saw some success but eventually floundered as “failure to assess and understand the poppy economy” misguided the programs.

Other, more radical suggestions include the licensing Afghan opium, so that it may enter the legitimate medical supply chain and perhaps go to developing countries which have an ongoing shortage of opioid medicines.

With Autumn approaching, the first indication of this year’s poppy harvest will soon be published, and it’s unlikely that opium production will top the record levels seen last year. But with the country weathering a massive drought which is decimating crops throughout Afghanistan, it’s also unlikely that foreign drug policies will be behind any reduction, despite what the US administration will inevitably claim.

The opium trade epitomises the war on drugs: a war which is growing ever more violent as it becomes less effective, with foreign institutions blindly imposing their will onto social structures they don’t fully understand. We can only hope that future drug policy will look beyond simply intensifying century-old anti-drugs strategies, and will instead look to the long-term welfare and wellbeing of society – both in the West, and in Afghanistan.

Nick Cherbanich

Podcast

- All

Links

- All

Support

- All

BIPRP

- All

Science Talk

- All

Amanda's Talks

- All

- Video Talk

- Featured

- 2016 Onwards

- 2011-2015

- 2010 and Earlier

- Science Talk

- Policy Talk

One-pager

- All

Music

- All

Amanda Feilding

- All

Events

- All

Highlights

- All

Psilocybin for Depression

- All

Current

- All

Category

- All

- Science

- Policy

- Culture

Substance/Method

- All

- Opiates

- Novel Psychoactive Substances

- Meditation

- Trepanation

- LSD

- Psilocybin

- Cannabis/cannabinoids

- Ayahuasca/DMT

- Coca/Cocaine

- MDMA

Collaboration

- All

- Beckley/Brazil Research Programme

- Beckley/Maastricht Research Programme

- Exeter University

- ICEERS

- Beckley/Sant Pau Research Programme

- University College London

- New York University

- Cardiff University

- Madrid Computense University

- Ethnobotanicals Research Programme

- Freiburg University

- Medical Office for Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, Solothurn

- Beckley/Sechenov Institute Research programme

- Hannover Medical School

- Beckley/Imperial Research Programme

- King's College London

- Johns Hopkins University

Clinical Application

- All

- Depression

- Addictions

- Anxiety

- Psychosis

- PTSD

- Cancer

- Cluster Headaches

Policy Focus

- All

- Policy Reports

- Advisory Work

- Seminar Series

- Advocacy/Campaigns

Type of publication

- All

- Original research

- Report

- Review

- Opinion/Correspondence

- Book

- Book chapter

- Conference abstract

- Petition/campaign

Search type