Support. Don’t Punish: Why We Need Drug Consumption Rooms

The link between childhood trauma and addiction is stronger than that between obesity and diabetes. A natural compassion compels us to make sure that a child who is suffering from abuse, neglect, or other traumatic experiences is properly supported. Too often, when these children do not get the help they need, they grow into young adults who turn to drugs to cope with, or to escape from, their pain. Among those who have no place that feels like home, some inject drugs in alleyways, at considerable risk to themselves and others, and society’s compassion gives way to impatience, prejudice, and stigma.

The stigma is cumulative and long-lasting. People with drug dependence elicit blame and fear, undermining employment opportunities and ultimately reintegration with society. It is in this context that Amanda Feilding and the Beckley Foundation supports the sixth Global Day of Action for Support. Don’t Punish, and, given recent hope that the UK’s drug policy might not forever be stuck in the 1970s, we urge the government to reconsider its obstruction of supervised drug consumption rooms.

Of the many harm-reducing policy improvements currently being taken up around the world, and rejected out of hand by Westminster, none encapsulate the Global Day of Action’s sentiment ‘Support. Don’t Punish’ as well as drug consumption rooms: hygienic, safe, and supervised facilities where people can inject their own drugs under medical supervision. Today, there are more than 100 drug consumption rooms operating across more than 60 cities worldwide, with more than 30 years since the establishment of the first facility in the Netherlands. Our first analysis of Drug Consumption Rooms was published in 2004, and since then, further research has contributed to a significant body of evidence, making the case for their introduction ever-stronger.

‘Support. Don’t Punish.’ seeks to leave behind the harmful politics, ideology, and prejudice that informs much global drug policy

There is no denying that drug injection leads to serious societal costs: it is a major contributor to the spread of blood-transmissible infections like hepatitis B and C, and HIV; and people who inject drugs more frequently develop other bacterial and viral infections, as well as psychiatric and other pathologies. The marginalisation that drug-injectors experience increases their exposure to homelessness and prostitution, and (in part because of its illegal nature), injection drug use can lead to an increase in violence, acquisitive crime, and the degradation of public spaces.

The prohibitionist rationale that underlies the typical response to such a problem seems plausible. Criminalise the possession of drugs for injection, and as drug use falls in response, so will the downstream harms. But this superficially plausible rationale does not hold up under scrutiny. National and international studies consistently fail to find a link between the severity of drug laws and rates of drug use. Moreover, minimising drug use has no necessary bearing on minimising drug-related harms. In seeking to achieve a ‘drug-free society’ in the 1990s and 2000s, Sweden invested its considerable drug policy budget into pursuing a fantasy, with little to show for it. Drug use was criminalised in 1993 to deter young people from starting. Experimentation with drugs among 15-year-olds tripled in the following seven years. And there were significantly more damaging consequences.

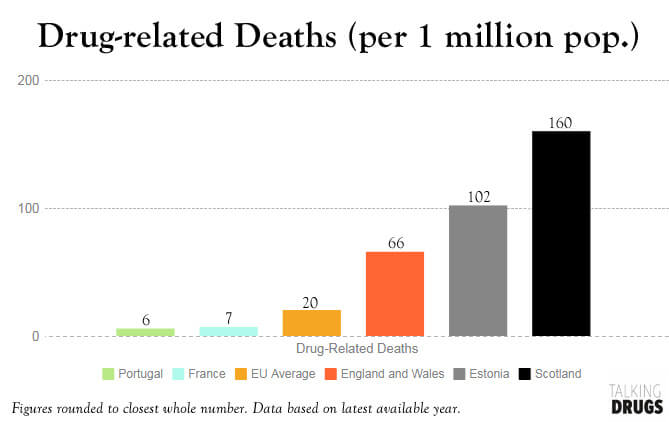

With harm-reduction interventions side-lined by the pursuit of an eradication of all drug use, injectors of drugs in Sweden suffer from one of the highest Hepatitis C rates in the EU. In 2016, Sweden recorded 87.8 drug-related deaths per million people. Not only was this some three times greater than the EU average, it was 22 times as high as Portugal, which since 2001 has emphasised a policy of harm reduction alongside the decriminalisation of drugs.

The UK fares little better than Sweden by this metric, with drug-related deaths increasing year-on-year, and doubling in Scotland over the last decade, and HIV-infection rates in Glasgow (the epicentre of the crisis) recently soaring 600%. In comparison, across a nine-year period, Sydney’s MSIC managed more than 3,000 overdose-related events, without recording a single fatality. In fact, no one has ever died from an overdose in a drug consumption room, and by providing clean needles and hygiene advice, drug consumption rooms have repeatedly been shown to decrease risky practices like needle-sharing that lead to health complications.

Driven by heroin and morphine-injection, rates of drug-related deaths in the UK, and especially Scotland, far exceed the EU average. Image courtesy of Talking Drugs.

These figures should give readers pause to question the stance of the UK government, who have repeatedly blocked both Holyrood, and a unanimous vote of the Glasgow Council, over the introduction of a drug consumption room in Glasgow. Although presented as a necessary action to protect society from the ills associated with drug injection, a more thorough evaluation of the available evidence highlights the indefensibility of this claim.

The first line of defence is that the introduction of drug consumption rooms amounts to the government condoning drug use or implicitly signalling its safety, thereby risking increased drug-taking. This is manifestly absurd. No one is under the impression that because the state facilitates the consumption of tobacco by regulating and licensing its sale, the government condones smoking or believes it to be safe. But more importantly, there is no evidence to suggest that the availability of drug consumption rooms is associated with an increase in drug use.

Nor, pace prohibitionists, do drug consumption rooms amount to ‘giving up’ on vulnerable individuals, acquiescing and enabling their self-destructive behaviour in lieu of helping them to free themselves from drug dependence. This is certainly a noble sentiment on paper, but fails to engage with the realities of working with vulnerable populations in general, and of drug consumption rooms in particular. Of course we should do what we can to facilitate a movement away from drug-dependence in those people who are able and willing to make positive changes in their lives. But in marginalised communities, who have suffered the most significant service cut-backs in the last decade, there remain many people with complex needs, perhaps blighted with poor mental health, unstable housing, and no plausible exit route. Among this group, there are those who are either unable or unwilling to attempt a recovery right now. Drug consumption rooms in other countries are often the only source of support for such people: as well as providing sterile injecting equipment and advice on hygienic injecting practices, they can provide a doctor or nurse for primary health concerns, counselling, and referrals to social and health-care services. Moreover, these services facilitate, rather than delaying, entry into rehabilitation and treatment programmes. Any politician that wants to see rates of entry into rehabilitation programmes increase should be in favour of introducing drug consumption rooms. They support, rather than undermine, the goals of addiction treatment.

Equally unfounded are concerns that the introduction of drug consumption rooms leads to an increase in crime. No such deterioration has been witnessed: in the neighbourhood of North America’s first drug consumption room in Vancouver, there has been no increase in drug trafficking, violent crime, or robbery, but the rate of vehicle theft and break-ins has declined. Use of drug consumption rooms is not associated with incarceration, and a number of studies of Sydney’s drug consumption rooms found no change in police-recorded thefts, robberies, or drug offences (including dealing) in their vicinity.

Discarded drug paraphernalia in a Glasgow street represent a serious hazard for all locals- photo from the Evening Times

What’s more, areas with high densities of drug-injectors often suffer from a high rates of public injection, and public disposal of used syringes. As well as drastically affecting the amenity of a public space, these practices represent a significant health risk for drug-users and non-users alike. Where drug consumption rooms are introduced, public injection, and public discarding of injection equipment significantly reduce.

By allowing drug-injectors to use of a safe, clean space, and by providing fresh needles, drug consumption rooms significantly reduce the incidence of HIV and hepatitis C infections. The most conservative estimates suggest that Vancouver’s Insite facility averts 35 HIV infections and 3 deaths per year. These avoided infections are associated with a net societal benefit of some $6 million in averted life-time medical costs, once the costs of running the programme have been taken into account: more than $5 saved for every $1 spent on Insite. This does not account for the extra savings and societal benefit to be reaped from reduced ambulance and police call-outs to overdose events. However it is calculated, Insite delivers a net saving to society.

“The evidence from 100 drug consumption rooms in ten countries worldwide could not be clearer: these sites represent an innovative development that can reduce HIV infections and eliminate overdose-related deaths, while encouraging more problematic drug users into rehabilitation programmes. With the UK likely to experience a record number of drug deaths this year, surely it is time to put evidence before ideology, and make the positive changes needed to save lives.”

-Amanda Feilding

Insite, in Vancouver, records an average of 415 injection room visits per day, and enjoys strong support among the local community. Image source: Brian Howell/Maclean’s

Drug consumption rooms are effective at reaching out to, and staying in contact with, the most marginalised populations. They do not lead to an increase in drug use. They do lead to increased uptake of addiction treatments. By providing a clean and hygienic space for users to inject drugs and dispose of syringes, they minimise the health risks associated with drug injection for users and non-users alike. In more than 30 years they have not to be linked to increased crime or public disorder. They have consistently been linked with lower rates of HIV and hepatitis infection. Not a single overdose-related death has been recorded at any drug consumption room, ever, and they are associated with significant savings in averted healthcare costs.

Drug consumption rooms are good for people who use drugs. They are good for people who do not use drugs. And they are good for the tax-payer. An impulse to pursue a punitive moral crusade can account for the continued obstruction of drug consumption rooms. A desire to support the most vulnerable, and society at large, cannot.

Support. Don’t Punish.

Eddie Jacobs

Podcast

- All

Links

- All

Support

- All

BIPRP

- All

Science Talk

- All

Amanda's Talks

- All

- Video Talk

- Featured

- 2016 Onwards

- 2011-2015

- 2010 and Earlier

- Science Talk

- Policy Talk

One-pager

- All

Music

- All

Amanda Feilding

- All

Events

- All

Highlights

- All

Psilocybin for Depression

- All

Current

- All

Category

- All

- Science

- Policy

- Culture

Substance/Method

- All

- Opiates

- Novel Psychoactive Substances

- Meditation

- Trepanation

- LSD

- Psilocybin

- Cannabis/cannabinoids

- Ayahuasca/DMT

- Coca/Cocaine

- MDMA

Collaboration

- All

- Beckley/Brazil Research Programme

- Beckley/Maastricht Research Programme

- Exeter University

- ICEERS

- Beckley/Sant Pau Research Programme

- University College London

- New York University

- Cardiff University

- Madrid Computense University

- Ethnobotanicals Research Programme

- Freiburg University

- Medical Office for Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, Solothurn

- Beckley/Sechenov Institute Research programme

- Hannover Medical School

- Beckley/Imperial Research Programme

- King's College London

- Johns Hopkins University

Clinical Application

- All

- Depression

- Addictions

- Anxiety

- Psychosis

- PTSD

- Cancer

- Cluster Headaches

Policy Focus

- All

- Policy Reports

- Advisory Work

- Seminar Series

- Advocacy/Campaigns

Type of publication

- All

- Original research

- Report

- Review

- Opinion/Correspondence

- Book

- Book chapter

- Conference abstract

- Petition/campaign

Search type