Do Psychedelics Make People More Environmentally Active?

Rawpixel.com/Shutterstock

The social and environmental activism that made the 1960s such an iconic and influential decade sprang from an existential shift in consciousness. Movements emerged based upon a new spirit of connectedness and unity, and as has been posited many times before, this sense of universal oneness was largely fostered by the rise in popularity of psychedelic drugs.

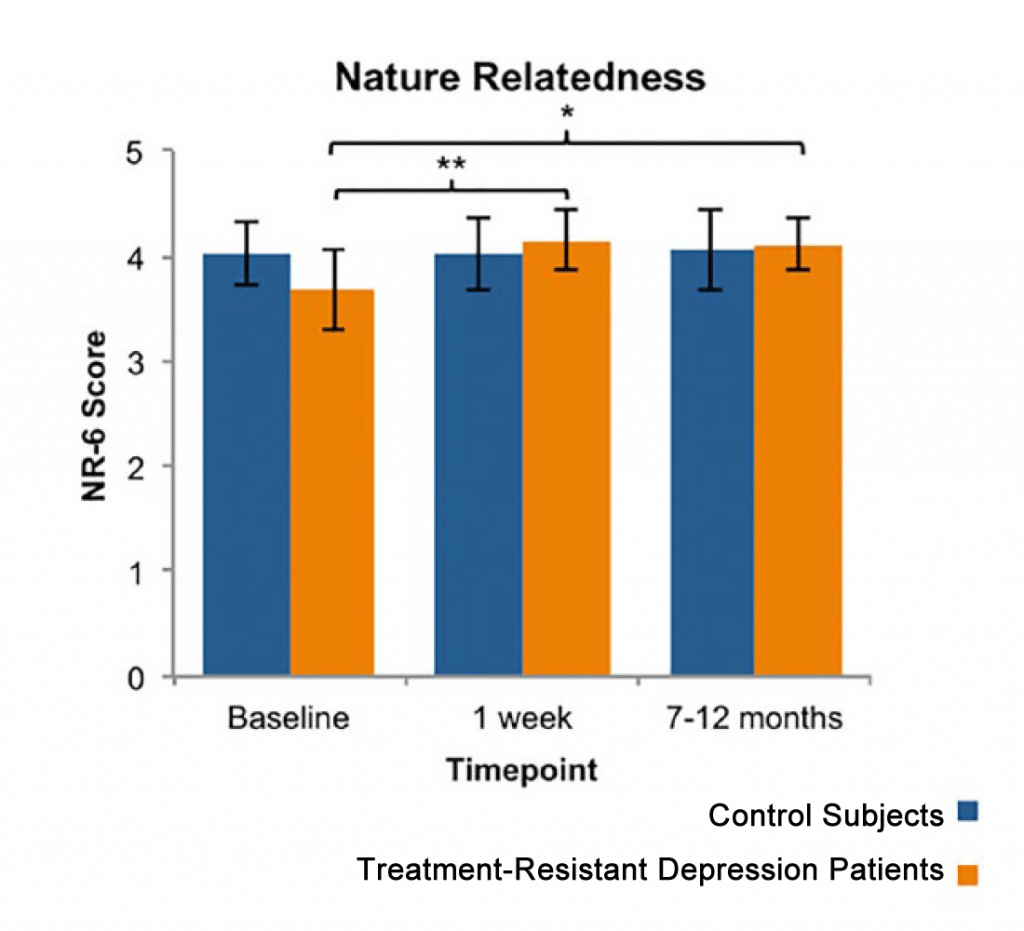

Half a century on, and scientists are still finding links between the use of these compounds and environmentalism. A recent paper from the Beckley/Imperial Psychedelic Research Programme found that following a psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy session, participants had significantly higher Nature Relatedness scores and an increased subjective sense of connectedness to nature.

In addition to the profoundly positive effect that the psychedelic therapy had in treating depression, the increased appreciation for the natural world may have indirect benefits; evidence from other studies suggests that greater nature relatedness is associated with lower anxiety and greater personal wellbeing.

Psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy resulted in an increased Nature-Relatedness score that persisted for many months following treatment (Lyons & Carhart-Harris 2017)

Another study published last year in the Journal of Psychopharmacology found that people who have taken psychedelics are more likely to engage in pro-environmental behaviours such as buying eco-friendly products, minimising air travel in order to reduce their carbon footprint, and adopting responsible water use practises.

According to the study authors, psychedelics “contribute to people’s pro-environmental behaviour by changing their self-construal in terms of an incorporation of the natural world.” In other words, psychedelic experiences don’t only change the way we perceive nature – they seem to leave people with a lasting sense of being connected to the environment, inspiring them to actively change their behaviours to better protect it.

These finding hark back to the early days of psychedelic research in the 1950s and 1960s, when scientists like Ralph Metzner began to write about how the powerful insights generated by substances like LSD, mescaline and psilocybin could help to bring about a new ‘ecopsychology’.

“Psychedelic experiences bring about an expansion of one’s sense of identity beyond the usual boundaries of our body-self,” Metzner once wrote. “Awareness may also expand outward into a greatly enhanced sense of interconnectedness with all life-forms in the great ecological web of life.”

And while prohibitive legislation may have prevented these compounds from fulfilling their revolutionary potential, the recent wave of research into their therapeutic power has added weight to Metzner’s argument.

For example, in a recent Beckley/Imperial study, two-thirds of patients with treatment-resistant depression were free of their condition three months after undergoing psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy. Follow-up analysis revealed that this improvement was largely catalysed by a sudden increase in feelings of unity with the wider world.

When asked to describe the psilocybin experience, one participant responded: “I felt like sunshine twinkling through leaves, I was nature.” Another summed up the sensation by saying: “this connection, its just a lovely feeling… this sense of connectedness, we are all interconnected, it’s like a miracle!”

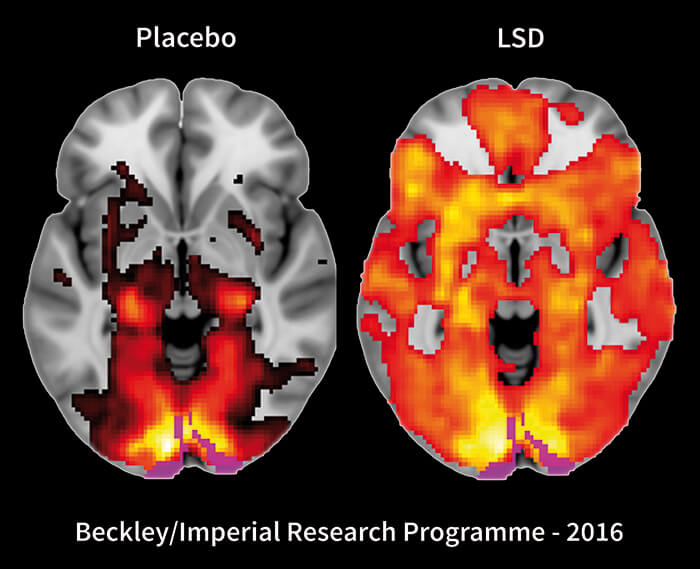

Brain scans produced by a recent Beckley/Imperial study reveal how LSD alters brain connectivity in order to produce an experience of ‘ego-dissolution’

Our ongoing research is looking into how psychedelics produce these particular insights, and how this can be harnessed in order to instill a new collective consciousness based on universal oneness, from which a new political, social and environmental order can emerge.

A major breakthrough in this field of scientific investigation was achieved in 2016 when the Beckley/Imperial Research Programme published the world’s first LSD brain imaging study. The scans showed how the compound reduces connectivity within a brain network called the Default Mode Network (DMN), which is heavily involved in maintaining a sense of self, and is sometimes described as the neural correlate of the ‘ego’.

At the same time, global connectivity throughout the brain increased, leading to a more integrated pattern of neural activity. These effects were strongly correlated with the subjective experience of ‘ego-dissolution’, whereby participants reported feelings of oneness with the universe.

Future studies will delve deeper into this phenomenon, investigating how the DMN can be targeted in order to break the rigid modes of cognition that underlie certain mental disorders. And while these studies will ostensibly aim to treat specific medical illnesses, the discoveries they yield could one day help to heal society on a more fundamental level by re-balancing our understanding of our place in the natural world.

Words: Benjamin Taub & Nick Cherbanich

Podcast

- All

Links

- All

Support

- All

BIPRP

- All

Science Talk

- All

Amanda's Talks

- All

- Video Talk

- Featured

- 2016 Onwards

- 2011-2015

- 2010 and Earlier

- Science Talk

- Policy Talk

One-pager

- All

Music

- All

Amanda Feilding

- All

Events

- All

Highlights

- All

Psilocybin for Depression

- All

Current

- All

Category

- All

- Science

- Policy

- Culture

Substance/Method

- All

- Opiates

- Novel Psychoactive Substances

- Meditation

- Trepanation

- LSD

- Psilocybin

- Cannabis/cannabinoids

- Ayahuasca/DMT

- Coca/Cocaine

- MDMA

Collaboration

- All

- Beckley/Brazil Research Programme

- Beckley/Maastricht Research Programme

- Exeter University

- ICEERS

- Beckley/Sant Pau Research Programme

- University College London

- New York University

- Cardiff University

- Madrid Computense University

- Ethnobotanicals Research Programme

- Freiburg University

- Medical Office for Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, Solothurn

- Beckley/Sechenov Institute Research programme

- Hannover Medical School

- Beckley/Imperial Research Programme

- King's College London

- Johns Hopkins University

Clinical Application

- All

- Depression

- Addictions

- Anxiety

- Psychosis

- PTSD

- Cancer

- Cluster Headaches

Policy Focus

- All

- Policy Reports

- Advisory Work

- Seminar Series

- Advocacy/Campaigns

Type of publication

- All

- Original research

- Report

- Review

- Opinion/Correspondence

- Book

- Book chapter

- Conference abstract

- Petition/campaign

Search type